I finally got around to reading a book I bought 5 years ago – “The Psychology of Architecture” by Lyubomir Kostron.

What is particularly interesting about this book? It was translated from Czech. I greatly miss books translated from other languages (I can read English and Russian without translation) – I want to know what other cultures and languages write about space, architecture, the psychology of relationships with the environment, etc. If you come across any interesting book, website, or podcast about space in any language – please let me know.

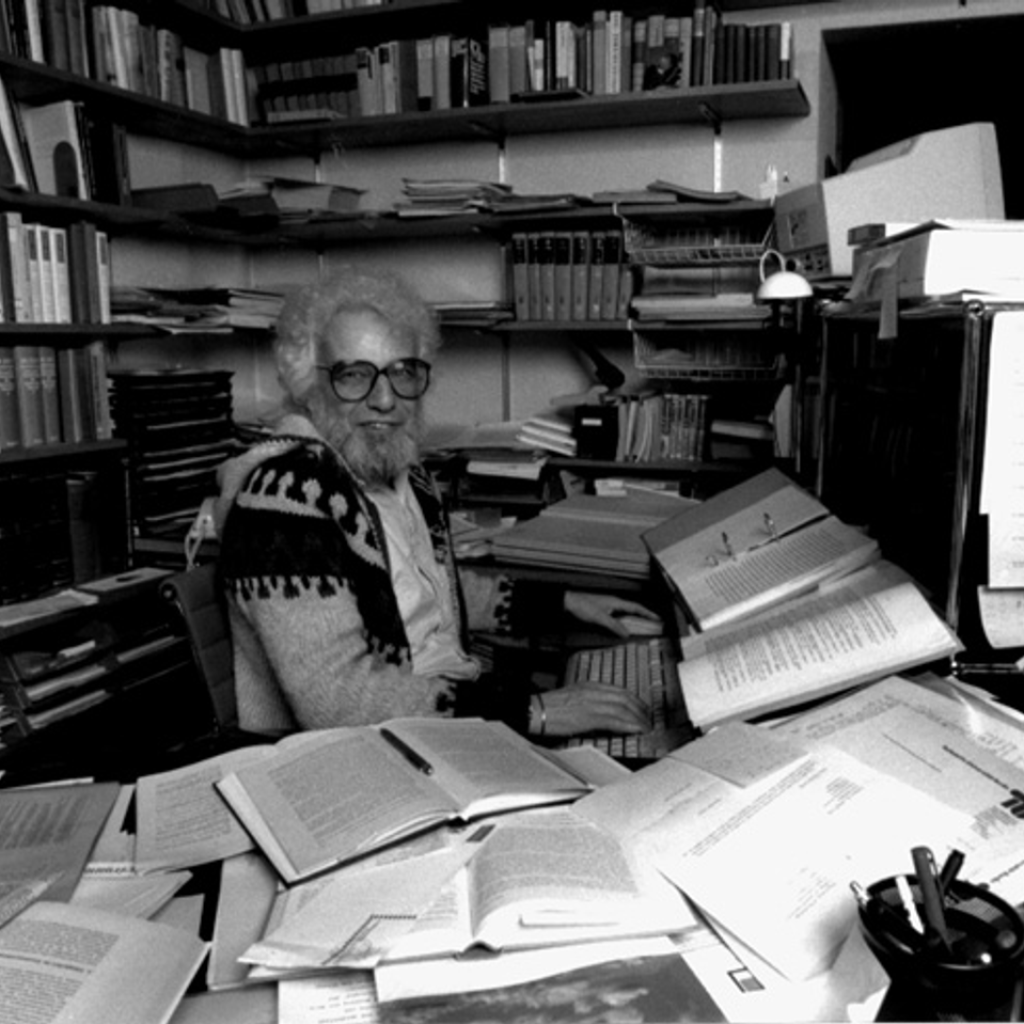

One of the first discoveries in Kostron’s book for me was Alfred Lang. The author mentions that Lang described an interview method in one of his articles, which his student used in her research, and I wanted to find this article to learn how it was conducted. I was lucky – I found the article (On the Knowledge in Things and Places, 1992), but unfortunately, it does not contain information about the interview itself, although the article is very interesting.

In this work, Lang writes about the process of INTERACTION between humans and the environment, emphasizing that space influences us, and we influence space. He calls this mutual influence the theory of trans-action. He also notes that we live in a world of things and places – “objects and spaces that bear meaning.” He even designates external space as “external memory” or “concrete mind,” highlighting the functional correspondence between the external (cultural environment) and the internal (mind). He also believes that the objects of psychological research should be human-environment systems or ecological units, which can be found in relation to simple everyday things, as well as to dwellings, institutions, neighborhoods, cities, and culture as a whole.

As an example of the study of the interaction between humans and things, he cites the work of his student Silvia Famos (1989). The work examines specific cases – the rooms of four young people. Both the artifacts themselves and their location (topography) in the present and the past are studied, as well as a structured interview analyzing the relationship with the five most important things. The theoretical premises for this research included Ernst Boesch’s symbolic action theory, Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton’s work on the meaning of things, and Lang’s own regulation theory of dwelling activity.

Lang believes that important objects for a person are located at non-random points both in the room as a whole and in relation to each other. Their placement is only partially determined by their functions or external characteristics; they are rather parts of a complex ensemble of meanings associated with the psychosocial identity of the person. Although most things identified as “special” are functionally passive, they manifest in the dialectic of thing-person, which can only be understood in a developmental perspective, where the location of things relative to each other undergoes subtle changes, as do the relationships between things and the person.

From the interviews with the study participants, Lang understood that the meaning and placement of these things are not always predetermined and not always realized. Participants are often surprised themselves, discovering the richness of connections between the thing and the room in terms of meanings.

Lang describes one of the cases where different areas of a person’s life activities are represented through five special items. The bed, somewhat hidden behind the door, symbolizes rest, recovery, safety, and generational connection; the violin, located close to the bed – in the most “personal” part of the room, is an important part of the room owner’s self-identity; plants serve both as a reminder of the parental home and as mediators of relationships with the sister; the crucifix demonstrates involvement in spiritual search; the painting, somewhat hidden from the eyes of those entering the room, symbolizes the search for personal relationships. It turns out that the bed is associated with the very meaning of home, the violin – with self-realization, plants – with social relationships, the painting – with partnerships, and the crucifix – with spiritual life. Each of these items occupies a separate part of the room, and together they form a non-random ensemble of a person’s relationship with the world.

In trying to outline the theoretical premises for his work, Lang speaks of two markers of his approach. The first is the study of the human-environment system, which he calls an ecological unit in evolution, and the second is the use of triadic semiotics (according to Charles S. Peirce) as a conceptual tool for describing and explaining the ongoing psychological process and its structure.

In personal space, objects surrounding a person turn out to be signs. Semiosis here is the process of using or creating signs, when in the triadic representational logic, the referent (object, source, etc.) and the representamen (physical object – carrier of meaning) are linked through the mediation of the interpretant (subject, agent, etc. – person).

Lang believes that perception and action can be viewed as prototypical sign processes: perception – intro-semiosis, creating signs in the brain; action – extra-semiosis, creating signs outside. Perception has referents in the world, while actions have referents in the structure of the brain. These processes can be called ecological semioses, and the approach to the human-environment system can be called eco-semiotic. The semiotic (triadic) concept is more complex than the usual symbolic representation, which involves only dyadic relationships.

Lang writes that while psychology has been interested in some aspects of the perceptual or intro-semiosis chain, followed by extra- or behavioral semiosis, it has, with few exceptions in social psychology, neglected pairs of extra-semiosis followed by intro-semiosis.

I found this thought of Lang particularly interesting and unusual: “One can say that in the first case, the world ‘speaks’ to itself through the mediation of a living agent. In the second case, a person ‘speaks’ to themselves or to other people through external channels and using messages transmitted by objects with their potential as representamen – to become referents.” The world speaks to itself through the mediation of a living agent – beautiful!

Lang further notes that communicative acts in the broadest sense imply two chain semioses. He concludes that all the above leads us to the possibility of a semiotic understanding of human interaction with places and things, thus going beyond the specific material, formal, or functional features of an object or space.

(In this work, Lang also mentions a study by Daniel Slongo (1990), in which the latter interpreted things and places in the house in terms of six general sign functions (referring to Karl Bühler and Roman Jakobson), but unfortunately, I could not find this work. If you find it, please share.)

While searching for the works Lang refers to in his article, I discovered Alfred Lang’s own website. Unfortunately, the site has not been updated for a long time – the author has long been deceased… But there is a huge amount of articles and various information on this site – I have not even had time to study everything yet. I hope the site will not disappear soon – and you and I will have the opportunity to get acquainted with the works of Lang and his colleagues.

Perhaps Alfred Lang is the progenitor of Ecological Semiotics, mentions of which can still be found quite rarely.

#psychologyofarchitecture #AlfredLang #semiotics #ecosemiotics #semiosis